Snorkeling guidelines in New Zealand encompass essential safety protocols and conservation rules designed to protect both swimmers and marine ecosystems. Key measures include utilizing the buddy system, wearing appropriate thermal protection like wetsuits for temperate waters, identifying rip currents, and adhering to strict no-touch policies to preserve fragile biodiversity.

What are the Core Principles of Snorkeling Safety?

New Zealand offers some of the most spectacular temperate water snorkeling in the world, from the Poor Knights Islands to the Goat Island Marine Reserve. However, the conditions here are vastly different from tropical destinations. Adhering to strict snorkeling guidelines is not merely a suggestion; it is a requirement for survival and enjoyment.

The foundation of aquatic safety lies in preparation. Before entering the water, every snorkeler must assess three critical factors: personal capability, environmental conditions, and equipment suitability. Unlike the predictable calm of a resort pool, the open ocean is dynamic. The “Alpine of the Pacific,” as New Zealand’s waters are sometimes called, requires a respect for cold water shock and rapidly changing weather patterns.

Furthermore, the ethos of New Zealand tourism is built upon the Tiaki Promise—a commitment to care for New Zealand, for now and for future generations. Your safety guidelines are intrinsically linked to conservation. By moving deliberately and calmly to conserve energy, you also minimize disturbance to the underwater environment.

How Do Wetsuit Requirements Change by Season?

One of the most overlooked snorkeling guidelines for international visitors to New Zealand is the necessity of thermal protection. Even in the height of summer, water temperatures rarely exceed 22°C (72°F), and they can drop significantly lower in the South Island. Hypothermia is a silent creeping danger that impairs judgment and motor skills long before a snorkeler realizes they are in trouble.

Summer Snorkeling (December – March)

During the peak season, the water is at its warmest, but “warm” is relative. For sessions longer than 30 minutes, a wetsuit is still highly recommended. A 3mm full steamer or a 3mm shorty is the standard guideline for the North Island. In the South Island, where water temperatures hover around 14-16°C even in summer, a 5mm suit is often necessary.

Beyond warmth, wetsuits provide significant buoyancy. This added floatation allows snorkelers to rest on the surface without expending energy treading water, reducing fatigue and the risk of cramping.

Winter and Shoulder Seasons (April – November)

Snorkeling in winter requires serious gear. Water temperatures can drop to 13°C (55°F) in the North and even lower in the South. The guideline here is strict: do not enter without a 5mm to 7mm wetsuit with a hood. A large percentage of body heat is lost through the head; a hood is essential for retaining warmth. Gloves and booties are also recommended, not only for warmth but to protect extremities from abrasion against rocks during entry and exit.

How to Recognize Rip Currents and Hazards?

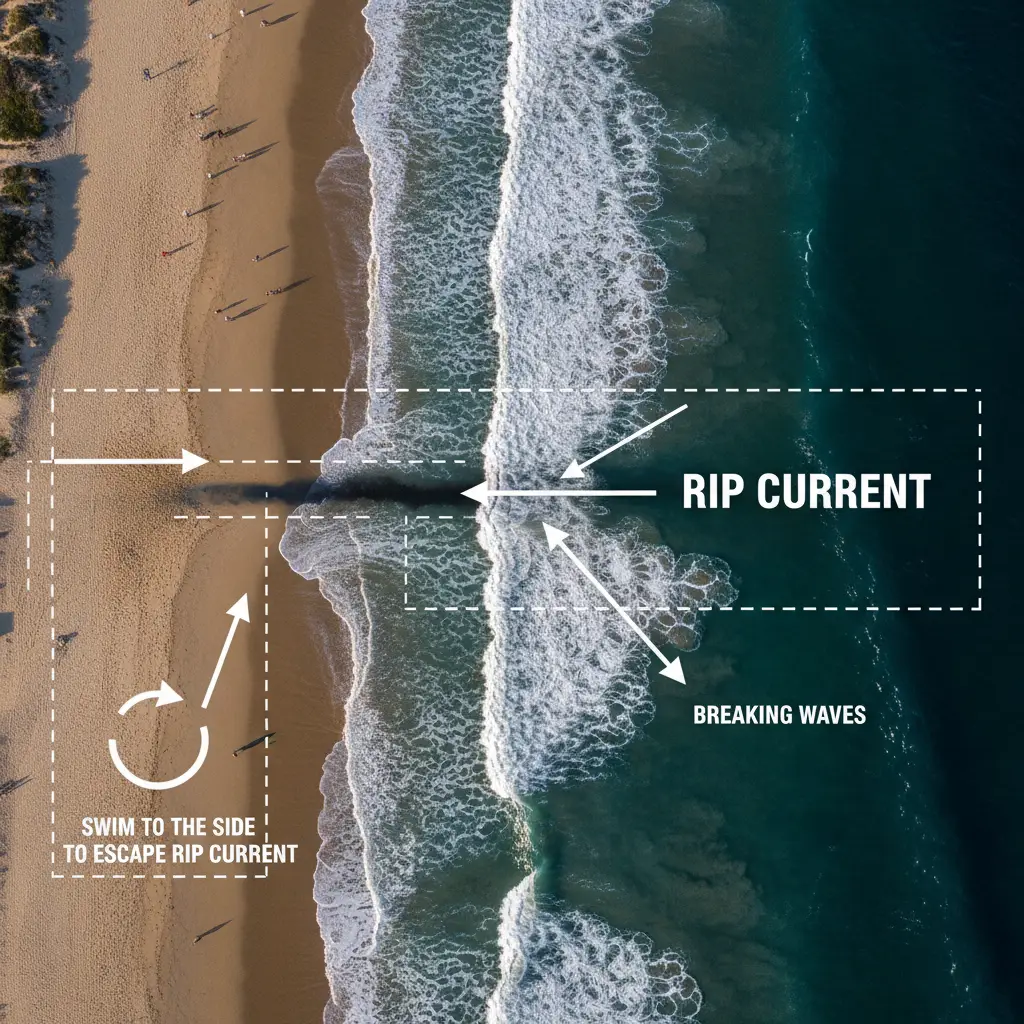

Understanding hydrodynamics is a critical skill. The most common cause of water rescue incidents in New Zealand is the rip current. A rip is a strong, narrow current of water which moves directly away from the shore, cutting through the lines of breaking waves.

Identifying a Rip Current

To follow safety guidelines, you must scan the water for at least 15 minutes before entering. Look for these signs:

- Discolored Water: Rips often churn up sand from the bottom, making the water look brown or murky compared to the surrounding blue/green water.

- The Calm Gap: This is a deceptive trap. A rip often looks like a calm path between breaking waves. Many inexperienced snorkelers choose this spot for entry because it looks easiest, only to be swept out.

- Debris Line: Seaweed or foam moving steadily seaward indicates a rip.

Escaping a Rip

If you are caught in a rip, the primary guideline is: Do not fight it. Panic and exhaustion are the killers, not the current itself. A rip will not pull you under; it will pull you out. Flip onto your back to float and conserve energy. Signal for help by raising one arm. If you can swim, swim parallel to the shore until you are out of the current, then head back to the beach. The current is usually narrow.

Why is the Buddy System Non-Negotiable?

Snorkeling alone is a violation of basic safety guidelines. The ocean is an unpredictable environment, and medical emergencies like blackouts, cramps, or equipment failure can happen instantaneously. The buddy system provides immediate redundancy.

The “One Up, One Down” Rule

For those who practice skin diving (diving down on a breath hold) while snorkeling, the “One Up, One Down” rule is mandatory. While one partner dives, the other remains on the surface, tracking their position and waiting for them to surface and breathe. This protocol ensures that if the diver experiences shallow water blackout, the surface buddy can intervene immediately.

Communication Signals

Effective communication is impossible with a snorkel in your mouth. Establish hand signals before you enter the water. Standard signals include:

- Thumb Up: “Ascend” or “Go up.”

- Thumb Down: “Descend” or “Go down.”

- Hand on Head: “I have a problem” or “I am okay” (depending on context, usually tapping head means problem in diving, but large OK sign is better for surface). Standard surface signal for distress is waving an arm.

- OK Sign (Thumb and index finger touching): “Are you okay?” and “I am okay.”

How to Respect Marine Life (Touching Rules)

In the context of New Zealand Eco-Tourism, snorkeling guidelines extend to how you interact with the environment. New Zealand is home to unique marine reserves where wildlife is protected by law.

The No-Touch Policy

The golden rule of eco-snorkeling is: Look, but never touch.

Many marine organisms, such as fish, have a protective mucus layer on their scales that prevents infection and parasites. Touching a fish removes this slime, leaving the animal vulnerable to disease. Furthermore, New Zealand’s rocky reefs are covered in fragile invertebrate life—sponges, ascidians, and bryozoans. A single careless kick with a fin or a grab with a glove can destroy decades of growth.

Interacting with Specific Species

Stingrays: Short-tail and Eagle rays are common. They are docile but possess a defensive barb. Never block their exit path. If a ray is on the sand, do not hover directly over it, as this may startle it.

Moray Eels: Often found in rocky crevices. They have poor eyesight and rely on smell. Never put your hands in holes or crevices to steady yourself, as an eel may mistake your fingers for food.

Equipment Checks and Maintenance

Equipment failure can turn a pleasant swim into a struggle. Adhering to maintenance guidelines ensures reliability.

Mask and Snorkel

Before every trip, inspect the silicone skirt of your mask for tears. A leaking mask causes panic. Check the snorkel keeper (the clip attaching the snorkel to the mask) for stress cracks. If you use a purge-valve snorkel, ensure the valve is clear of sand. A single grain of sand can prevent the valve from sealing, causing you to inhale water.

Fins

Check the straps of your fins. Rubber degrades over time, especially when exposed to UV light and salt. Pull on the straps firmly before putting them on to ensure they won’t snap in the water. If you are snorkeling in rocky areas (common in NZ), open-heel fins with booties are safer than full-foot fins, as they protect your feet when walking into the water.

What are the Emergency Protocols?

Despite best efforts, emergencies occur. Knowing the guidelines for self-rescue is vital.

Cramps

Leg cramps are common in cooler water. If a cramp strikes, do not panic. Roll onto your back to keep your airway clear. Grasp the tip of the fin on the affected leg and pull it toward you to stretch the calf muscle. Signal your buddy immediately.

Lost Buddy Procedure

If you lose sight of your buddy, the guideline is: Search for one minute underwater (rotating 360 degrees), then surface. If you do not see them on the surface, wait briefly, then call for assistance. In a guided tour scenario, alert the guide immediately.

People Also Ask

Do I really need a wetsuit for snorkeling in New Zealand?

Yes, in almost all cases. Even in summer, New Zealand waters are temperate, rarely exceeding 22°C (72°F). A wetsuit provides essential thermal protection against hypothermia and offers added buoyancy, which is a critical safety factor for fatigue management.

Is it safe to snorkel alone in New Zealand?

No, snorkeling alone is strongly discouraged. The ocean conditions in New Zealand can change rapidly, and currents can be unpredictable. The buddy system ensures that someone is available to assist in case of cramps, equipment failure, or medical emergencies.

What is the ‘look but don’t touch’ rule?

This is a conservation guideline protecting marine life. Touching fish can remove their protective mucus layer, leading to infection. Touching coral or sponges can physically damage or kill fragile organisms. It ensures the ecosystem remains intact for future visitors.

How do I identify a rip current from the beach?

Look for a channel of water that appears calmer or flatter than the surrounding waves, often with discolored (sandy) water or foam moving out to sea. This “calm” gap is actually the dangerous current moving away from shore.

Can I take shells from marine reserves in New Zealand?

No. In a designated Marine Reserve, it is illegal to remove anything, including shells, rocks, driftwood, or sand. Everything is protected to allow the ecosystem to function naturally. Heavy fines apply for removing items.

What should I do if I get caught in a rip current?

Do not panic and do not try to swim against the current back to shore. Float on your back to conserve energy, raise one arm to signal for help, and if you are able to swim, swim parallel to the beach to escape the narrow current before heading back to shore.